In a blog post, Morgan Housel provides an entertaining description of business which a friend of his, Brent Beshore offered. Beshore views business like eating glass while being punched in the face. He states, “Often nothing works. Emotions run wild. Confusion reigns.” Beshore goes even further suggesting that business can be a daily battle “where you wake up every morning, grab your knife, fight off challenges, and pray you make it home alive.” Sounds more exhausting than exhilarating.

A survey undertaken in 1999 may offer support for the perspective that work environments can be challenging. The survey asked employees of organizations their perspective on the following question: “Do you feel your organization is managed: like an orchestra, like a medieval kingdom, or like a three-ring circus?” It’s an amusing question. The question was asked of employees at all levels, from entry-level front line workers to higher levels of management. The latter two less flattering responses, Kings and Clowns, were chosen by 59% of management and 72% of the balance of staff. Apparently, not many musicians were in the crowd of respondents. The same research study, somewhat unsurprisingly, reported that 38% and 47% of managers and employees, respectively, were dissatisfied in their jobs. The study’s takeaway concluded that people aren’t thrilled to work for either Kings or Clowns. Moreover, the optimal outcome of orchestra was far and few between.

These aren’t optimistic results. They suggest dissatisfaction at all levels with work lives. Sadly, the data gets worse. A separate survey found that 61% of managers and 65% of employees were discussing looking for work outside their current organization. Even if this percentage of staff are just discussing what they may do or would like to do, it suggests they aren’t bringing their best energy or full effort to the task at hand. At best they are acting like dogs being dragged as opposed to leading with full energy forward.

How would you answer for your organization? Do you feel your organization is managed like an orchestra, a kingdom, or a circus? How would your colleagues answer?

Business consultant and author, Martin Lindstrom, when meeting with clients performs his own version of a Rorschach Test in order to get a sense of what kind of culture an organization has. He shows people a couple of pictures and asks “Which of these photos most accurately describes how it feels to work here?” In The Ministry of Common Sense, Lindstrom writes about his approach to evaluating a company’s culture. On one card is a picture of a person trapped inside a narrow, confined space. The other picture shows two parents yelling at a child. From these pictures people seem to relax and open up in their discussions about their organizations. Lindstrom’s pictures capture companies devoted to direction, micromanaging, and clear command and control structures. The harsh pictures can stimulate a conversation where people offer their own interpretations of the approaches to leadership within their companies.

In a similar vein, Business Professor at USC on Organizational Culture David Logan, offers five stages of tribal leadership. Logan’s experience suggests all teams fall along a spectrum of five levels. Level 1 is the lowest and reflects helplessness and despair, things suck. This is the level of leadership seen in prisons for example. That sounds worse than a circus. Level 2 isn’t much better. Here things are pretty bad, team members feel like their role stinks. They aren’t respected. Their ideas aren’t considered. They believe nothing will change. Unfortunately, Logan considers around 25% of workplaces like this. Level 3 is more like our Kingdom. These environments are noted for their competitiveness. These are zero sum games where some get ahead but do so at a cost to others. The environment may function, but trust isn’t high. At level 4, things start to be productive and pleasant. Culture benefits from collaborative efforts. Team members get along and go along and the organization progresses. We’re now in our orchestra stage. Logan’s level 5 is the peak of this type of culture where people’s personal aspirations match those of the organization’s. Both work together seamlessly. This is rare air and almost aspirational.

Many things in the business environment have evolved over the years. One of these is the way that leaders wield authority. Back in “the good old days,” when a leader said “jump,” the only acceptable answer was “how high?” Leaders were the unquestioned boss. If they said “sit down,” your job was to stop and drop right then and there without even thinking to look for a chair. As the top down hierarchical structure ceased to be the only method of leading, flatter organizations became the rage. Now leaders approached their staff with a bit more balance. This generation of leaders made requests as opposed to barking orders. A leader may invite us to do something. “Please, take a seat,” they would say after ensuring that there were chairs present for all attendees. Then servant leadership became a fashionable perspective. It seemed to swing wildly to the other end of the continuum where leaders have morphed from caveman characters grunting uni-directional imperatives to becoming like a Maitre’d at a fine restaurant. When they said, “please, take a seat,” they were assisting their staff into their chairs. Or, staff now felt on more equal footing with leaders and could push back instead of acquiescing to a request. In reply to, “please, take a seat,” responses like, “why?” or “for how long?” or “sitting is bad for me, I need an ergonomic stand up desk.” Authority has morphed from absolute to a lot less.

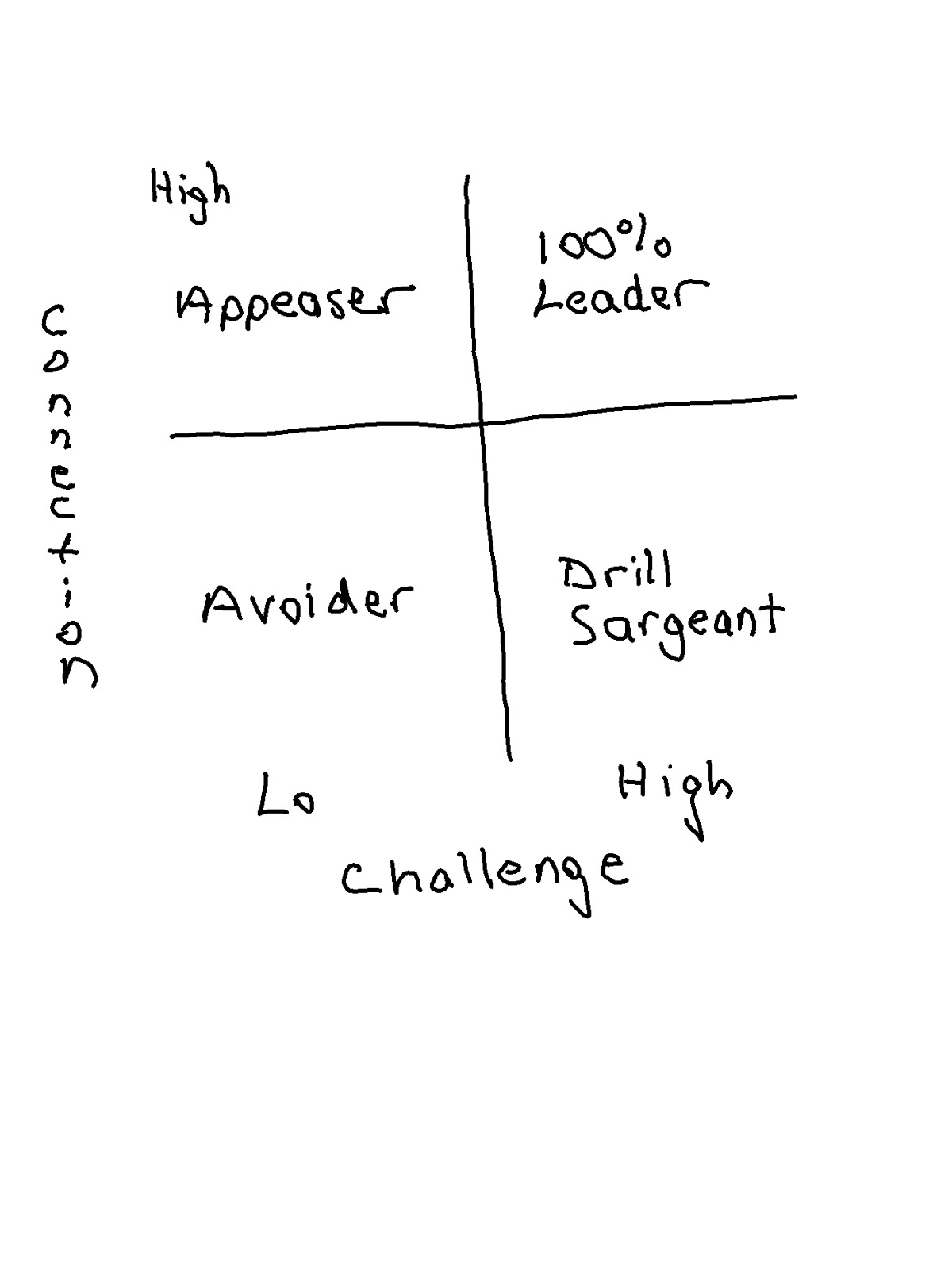

There remains a number of different leadership types. Perhaps, you’ve had experiences with one or more of these or even other kinds. Have some forms of leadership resonated more for you? If you’re a leader, what path are you trying to pursue? Mark Murphy offers a useful framework to help us see the different way those in charge can behave. In his book, One Hundred Percenters, Murphy distills the key dimensions of leadership into two traits: challenge and connection. These two traits can provide four leadership types. There are those that consider connection with staff a low priority and those that consider it a high priority. So, too, it is with challenge. There are those that see challenging staff as a low priority and those that see it as high in importance. It we graph Challenge on the X axis and Connection on the Y axis, we can create a quadrant with four boxes of leaders.

In the bottom left box, we have leaders that view both challenge and connection for their staff as low priorities are considered Avoiders. They are dis-interested. They don’t care about the people working for them, nor do they care about their staff’s development. They barely care about the business at all. These kinds of “leaders” happily delegate everything but their desk. They enjoy their position, their title, but that’s about it. Performance in these environments tends to be quite low. It’s a leadership approach that can only be sustained in established organizations buried deep in bureaucracy. Any positive performance in these cultures is more the result of luck than leadership. People are left to flounder and figure things out on their own. Employee engagement suffers and turnover grows as a result.

Moving to the box to the right, we have leaders more like our original type. These are the drill sergeants. They push and push with little regard for their people. People are replaceable cogs and must be used to their fullest. Mission first, all else in service of the mission. These leaders pursue performance over people. They consider folk fungible, corporate cogs that can be replaced by the next in line. They happily send line after line of infantry over the wall and into enemy territory, willingly sacrificing their staff for the immediate burst of effort they can suck out of them now. These kinds of leaders are like the teacher from the movie Whiplash. He’s so intense, so committed to creating perfection in his music group. He wears down and tears down musicians in order to serve his purpose. In a peak moment in the movie he reveals his true character stating, “There are no two words in the English language more harmful than ‘good job.’” These leaders believe what individuals contribute is never enough and the mission matters more than those that contribute to it. In All-In, authors Adrian Gostick and Chester Elton write of various organizational cultures. They introduce us to a professional from a consumer products company that offers, “Around here they put a gun in your back on day one. The trigger is pulled, and if you stop running the bullet is going to get you.” This is the mentality of leaders hyper-committed to challenge while ignoring connection. These types of leaders may be one hit wonders. They may generate solid performance in the short term. However, their staff suffer from burnout and high turnover.

Moving to the top row, left side box, we have Appeasers. These leaders love their people and want to be their best friend. However, they won’t challenge them. They are true servants. They aren’t leading from behind. They aren’t leading. They are serving their staff. This approach, like the avoiders, suffers from poor performance. Accountability is absent. Training opportunities are far and few between. Those that are eager and ambitious learn quickly the environment isn’t for them and head for the exits. Those that stay behind are mediocre performers. They may like where they work, but the operation slides along on borrowed time. Environments led by appeasers result in places which look from the outside as ones where the inmates are in charge of the institution. Managers are like substitute teachers and they’re trading teaching for babysitting. Appeasers believe it’s better to get along than to get ahead.

Finally, we have Murphy’s One Hundred Percent leader. These are those that can find the balance of both connecting with staff and challenging them. These leaders are engaged and purposeful as are their employees. Gostick and Elton observe, “The most profitable, productive, enduring cultures are cultures where people believe. Where people lock into a vision with conviction, where they maintain excitement not out of fear but out of passion.” Effective leaders expect the best from their team. They recognize that one of their responsibilities is to push hard to encourage the extra effort required to achieve desired results. However, they recognize they and their team can’t run in the redline perpetually. The best leaders are empathetic enough to see when extra effort is being met with diminishing returns. As the late, great football coach, Bill Walsh writes in The Score Takes Care of Itself, “There has to be a very acute awareness on your part as to the level of exertion and the toll it’s taking on those you lead.. The art of leadership requires knowing when it makes sense to take people over the top, to push them to their highest level of effort, and when to take your foot off the accelerator a little.” It’s not all on all the time. These leaders have found the sweet spot for both connecting and challenging others in the organization. Walsh notes, “The best leaders are those who understand the levels of energy and focus available within their team.”

Can you think of leaders from your past that you’ve worked with that would fit any of these four categories? Where does your culture stand? How do you know? Consider the following statements from the perspective of your workplace.

In a Low Challenge environment, staff would agree or strongly agree with the following types of statements:

Our best people don’t stick around.

Accountability is absent in our organization.

Our leaders don’t seem focused or aware of challenges and opportunities in the industry.

Our standards of professionalism are low.

Our direction isn’t clear. The status quo seems to be the goal.

In a Low Connection context, staff would agree or strongly agree with the following kinds of statements:

Management and operations are separated. We sit in different spaces and don’t share information.

Workplace behaviors include politics, posturing for position, backstabbing, and blaming.

Trust between team members is low.

Staff functions, if they occur at all, are forced and uncomfortable.

In a High Connection context, staff would agree or strongly agree with the following:

This is a fun place to work.

My manager knows about my personal life.

In a High Challenge/High Connection environment, staff would agree or strongly agree with the following:

My manager and I work together to create clear performance objectives.

We operate in a performance based environment.

The left hand knows what the right hand is doing in our organization. Our departments’ efforts are aligned.

Our leader checks in regularly to ensure we have what we need to do our job.

My manager understands the challenges we face and provides support.

Our leader communicates constantly and consistently about our organization’s direction and the importance of our contributions to its success.

My manager asks about and supports my long term career aspirations.

Conversations around performance are based on the desire to improve and not about assigning blame.

I feel appreciated as a valued member of a winning team.

As Gostick and Elton write, “It is culture that is driving whatever you are trying to accomplish within a company… There are workplaces of outright dysfunction, of contention, of coasting, and even of backstabbing.” The culture of an organization follows the actions of a leader. The leader sets the tone of what will be tolerated. In a future article we’ll offer a perspective of leadership traits that tend to be found in those successful at finding the sweet spot of high challenge and high connection for their organizations.