If you remember learning to drive or have enjoyed the privilege of supervising a teenager learning to drive, you may be familiar with the challenge of driving in a straight line. It’s not quite as simple as just locking the steering wheel with the wheels pointed straight ahead. The car or road inevitably drifts slightly left or right. To drive in a straight line we need to continuously make modest adjustments to the steering wheel. Through slight movements to the right and slight movements to the left, the adjustments are constant, resulting in keeping the car steady and stable. The mark of inexperience and absence of skill is both wider and more abrupt adjustments. When we’re learning to drive our adjustments are not subtle. The over exaggerated movements jar the car and send passengers into fits of nausea. It’s definitely disconcerting to be a passenger in this type of experience. We’re not lulled into sleep when lurching side to side within our lane. It’s a drag to be in a car that zigs and zags. If the shortest distance between two points is a straight line, then we’re driving a lot further with an inexperienced driver.

Maybe you recall being instructed in a driver’s education course that the objective, for example, while changing lanes is to do so smoothly such that a passenger not paying attention or having their eyes closed wouldn’t know that the car changed lanes. We’re introduced to learning to drive first at slower speeds where the required adjustments can be managed easier. We’re taught to look further ahead down the road and not immediately over the edge of the hood of the car. We’re given points of reference to look at, like the solid line marking the edge of the lane and start of the shoulder on our side of the road. We’re taught to keep our arms loose and to find the feeling of constant adjustments. The combination of the guidance and practice helps us smooth out the path of our vehicle.

Finding and holding the center of a driving lane is neither certain nor easy. It requires ongoing attention, effort, and skill to manage this task smoothly.

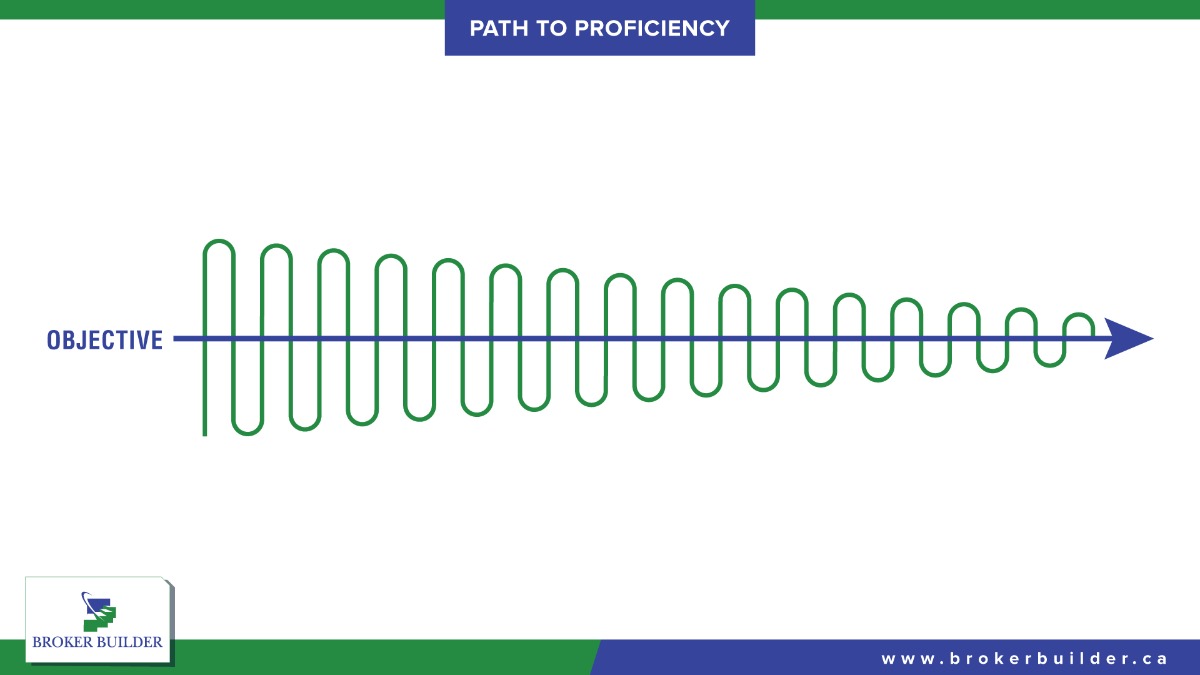

Out moto-metaphor applies to all types of learning. The performance of beginners will be considerably off the target. The greater the adjustment required, the more noticeable they will be. Additionally, the greater the adjustment required, the more unpleasant an experience. The more unpleasant the experience, the greater the resistance to participation. We want to avoid these kinds of learning experiences. However, as we practice and improve, our results improve. We are able to achieve the desired standard once in a while. With additional practice, the reliability of our performance improves. We’re now able to demonstrate the skill regularly under a wide range of conditions. When we decrease the depth of deviation we demonstrate proof of proficiency.

The idea of striving toward an objective, over shooting, course correcting, striving back toward the objective, and over shooting in a different direction applies to our aspirations not just in learning, but also with respect to working toward objectives. Aristotle’s concept of the Golden Mean involves finding the balance point between two extremes. The value or virtue is found as a moderate balance point between two more extreme behaviors. We struggle toward our ideal point by swinging too far left and too far right. We clamor crudely back and forth, over and across our objective, striving, touching, but not sticking to our goal. Our goal isn’t perfection, but less variance. When working with objectives which are ongoing, we remain in constant motion like our car. The adjustments, too, will be continuous.

How can we help ourselves stay on track?

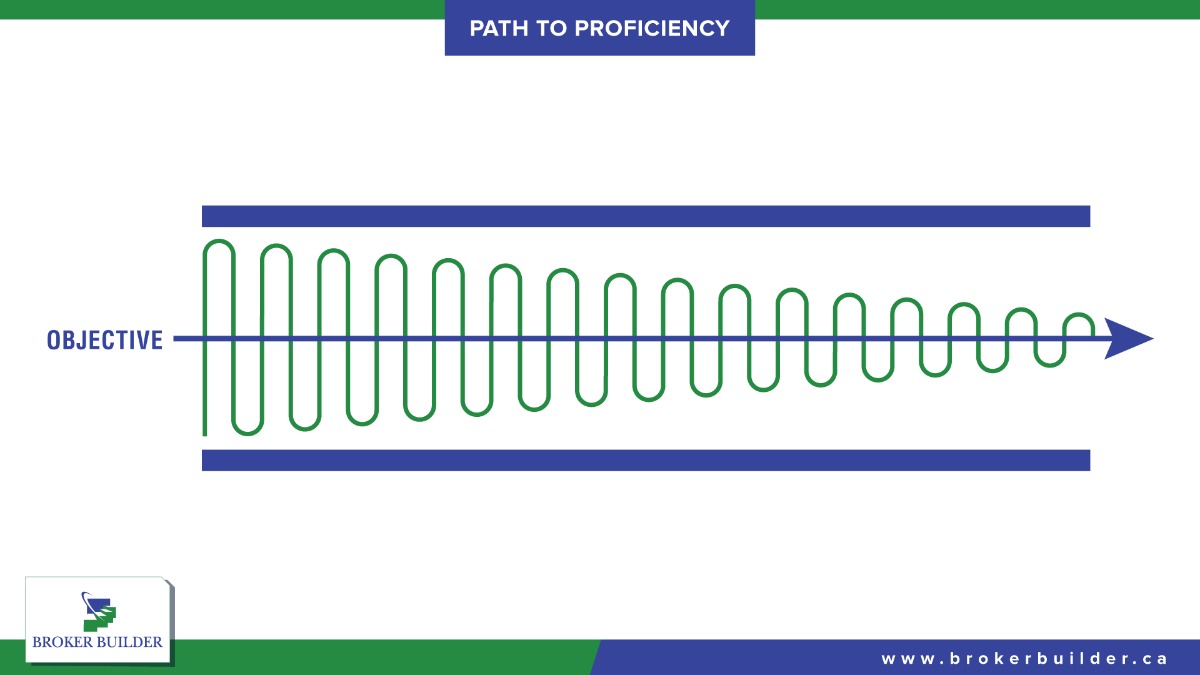

Many amusement parks include a ride which provides kids with the experience of driving independently. Very young kids are able to either sit on their parents lap or on their own in full control of both steering wheel and a gas pedal. The child may not know it but the vehicles are placed over a single rail. This limits the amount of deviation from the lane that is possible. Even if a driver holds the steering wheel hard to the left, the vehicle can only go so far to the left as the rail will force the vehicle to move forward instead of further in the direction of the steering. The rail limits how far off the desired path the car may travel. This ensures the car ultimately stays on track. Rides like this also impose a governor limiting the speed of the car. There is a final protection which controls the distance allowed between the car ahead and that behind. All of these are guardrails which keep the car on the road making the experience enjoyable for the young ones enjoying their “control”. In a separate example, beginners of bowling may enjoy the benefits of guard rails that can be set up to keep balls rolling towards the pins. The guard rails come down and block the gutters. Beginners avoid the frustration of having their balls repeatedly drop into the gutter. The sport becomes immediately pleasant and rewarding. The success experienced draws the player in asking for more.

These types of boundaries serve two primary purposes. They serve as guard rails protecting us from dangers. They also act as limits to how far off course we can go. Whether we view these as guard rails protecting us from dangers or guide rails that are steering us in the right direction, finding things that help us stay on track is a good thing.

Staying safe and on course are desirable outcomes. We can thank those that know more about us in an area for putting guardrails in place for us. However, these guardrails can become hurdles to our progress. We can come to depend on the guardrails and want them to remain in place. We happily roll our ball at the gutter rail with confidence that it will reliably roll over a few pins. Our learning isn’t improved. We don’t become better at aiming our ball down the center of the lane. We have no reason to improve as the guardrails keep us in track. The protections, though well intended, create a cost to learning. A separate barrier these guardrails may offer is that users may not be aware of them. Where users don’t recognize a guardrail is in place, they fail to recognize the disconnect between their action and outcome. They develop a false sense of proficiency as to their capabilities. In our amusement park example a child may not realize there’s a rail under their car keeping them on the desired course. If they don’t realize this, they will begin to think they are actually capable of driving.

The purpose of pursuing proficiency isn’t perfection. We’re not reasonably seeking performance with 100% accuracy 100% of the time. We evidence expertise when we deviate less from our desired outcome. We’re working to deliver performance which is closer to the desired target. Sure, we’d like to hit the bullseye all of the time, but we’re trying to keep our darts on the board first and foremost. The thermostats in our homes don’t work to keep the environment static. There’s a range of acceptable temperatures both above and below the set value that can occur before the thermostat triggers the furnace or A/C to kick in. It’s the same with the cruise control in our vehicles. We may set the value, but the car’s speed won’t hold it perfectly. The speed will be slightly higher or lower and maintain the target on average. We’re seeking a similar outcome with our efforts.

For example, when working toward a more subjective outcome like allocating autonomy to staff, the idea of ongoing adjustments remains useful. We will be moving to and from autonomy. Our efforts may shift to micro-managing until we realize we’re doing it and causing problems, then we’ll move away from micro-managing back toward autonomy. We may then take our hands off the steering wheel and let things slide over to the other side toward abandoning our staff. Again, this will somehow be drawn to our attention and we’ll reengage, providing some direction and clarity to our staff which allows them to strive toward autonomy. It’s a steady swing. The guidance we offer our staff isn’t one and done. Nor is it none and we’re gone. It’s ongoing and iterative. Our employee handbooks and Work Instruction Procedures (WIP) aren’t set in stone and left alone. We are updating these regularly based on our learnings. We develop improved practices based on staff and customer feedback. We encounter experiences we hadn’t considered and develop workflows to manage these. This is how we swing back and forth through our objectives. Many factors are at play in our management efforts. It’s a long and winding road that requires reliable effort to stay on track allocating autonomy.

Our learning is assisted and accelerated with awareness. We can pave the path to proficiency by building awareness. Our heightened awareness can increase sensitivity to deviations from our path. We become better at alerting ourselves to our drift. Establishing and implementing guardrails are an essential aspect of both learning and change efforts. Progress in both follows high levels of awareness. Roy Baumeister in his book, Willpower, writes, “The more carefully and frequently you monitor yourself, the better you’ll control yourself. The dreaded scale can be a blessing or a curse to our weight loss or control efforts. If we’re seeing movement in the desired direction, we remain motivated and committed; but if we see things slipping, we can fall off the rails of our efforts. To help us, we can work to target a range. We should recognize our weight will naturally fluctuate several percent day to day. Weight change from day to day or within a day is less meaningful than tracking how we’re doing week over week. We can use the scale to provide guard rails that work to keep us constructively focused. Our goal is to maintain a weight within a range of values that shows some decrease over time as opposed to consistent and continued declines which are unrealistic.

Shane Parrish of The Knowledge Project offers the suggestion of setting “tripwires” around objectives. Tripwires are predefined indicators that when hit provide feedback to a business as to whether the activity should be continued or not. For example, if a new sales initiative is being pursued, a sales target could be set as a tripwire. If new sales of $10,000 are achieved within 60 days, the initiative will continue to be pursued, otherwise the effort will be discontinued. This could also be applied in a business context as setting tolerances for quality of product output. Consider running spot audits on insurance applications internally. If a certain number or percentage of those reviewed contain an error, then training is warranted. This would set a downside limit to workflow errors and protect the range of quality output. We’re trying to set triggers to help us stay on course. Are we confident that we’re moving closer to our desired target? How do we know? We want to track negative performance indicators that suggest intervention is implied as well as positive performance indicators that tell us we’re doing well. The positive indicators warrant either celebration or additional investment whereas negative indications require management intervention to resolve.

When we’re considering a new project, take time to define what success looks like, then consider how you will be able to monitor progress. What will it look like if you’re making progress toward desired outcome? What will it look like if things are slipping sideways? At what point is intervention implied? Investing energy creating clarity around both the desired outcome and tolerance for performance above and below the target will build a solid foundation from which learning will be accelerated by smoothing out the speed bumps on your path to proficiency.

One thought on “The Path to Proficiency – Learning to Drive”

Comments are closed.